Anti-LBGTQ Legislation, Policing, and Harassment

By the 1950s, San Francisco had a distinct queer community, centered around Polk Street in the North of the city. But even as new queer spaces continued to appear and the community coalesced around these bars, governmental agencies worked to regulate and discipline queer life. A slew of new legislation in the 1950s radically changed the way queer people and places were policed. Media coverage of queer people also intensified during this period, resulting in an increasing public awareness of “abnormal” sexuality, and growing calls to policing agencies to crack the whip to protect American families.

San Francisco Examiner, 28 June 1954

In California, it was illegal for gay people to gather in public places, or be served a drink. There were fierce laws prescribing jail terms of up to ten years for committing a homosexual act. Legislation and Homophobia meant queer people were already forced to be discreet about their sexuality, but police Vice Squads made concerted efforts to “catch” them. Police staked out homosexual hangouts and frequently raided gay bars, charging patrons with disorderly conduct, cross-dressing, and other minor offenses. By 1961, 40 to 60 homosexuals per week were charged in the San Francisco courts with some crime relating to their sexuality, and over a dozen gay bars had been shut down. The constant threat of raids also meant continual fear of exposure for gay people in San Francisco, as the names of arrestees were printed in the local newspaper, often outing them to employers and families.

A police officer at San Francisco Pride, 2008. Although police departments now regularly march in Pride parades, uniformed participation is controversial. In 2022, the SF Pride Board initially banned marchers in uniform as a sign of support for those who continue to feel unsafe in the presence of the police. Credit: cop4cbt, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

“Straight cops patrol us, straight legislators govern us, straight employers keep us in line, straight money exploits us. We have pretended that everything is OK, because we haven’t been able to see how to change it — we’ve been afraid.”

The Castro as Battleground

As a gay enclave began to solidify in the formerly Irish-Catholic Eureka Valley in the 1960s, clashes between the new Castro residents and conservative Irish police were common. Two radically different populations were now living in Eureka Valley. Straight residents fought back against the gay “onslaught” using violence and vandalism. An exclusive neighborhood business association, The Eureka Valley Merchants Association, conspired to out gay business owners. An early 1970s California Scene article notes that around Castro Street, “local residents have gotten uptight, the police are beginning to drop by the [gay] bars and roving gangs of youths (possibly taking their cue from their parents) are beating up gay guys on their way home at night.”

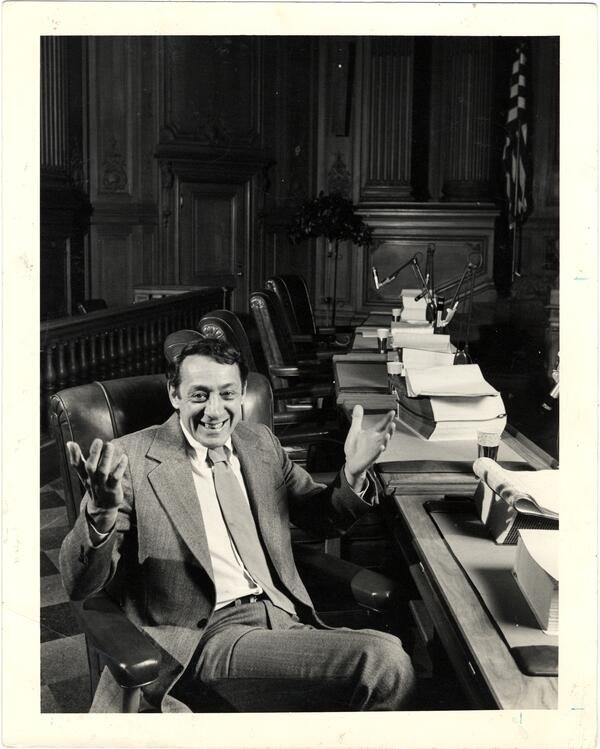

Harvey Milk’s election to city-wide office was in many ways a vindication of a gay-rights strategy that focused on protesting and organizing within the mainstream political system, rather than aiming to dismantle these structures.

Credit: Harvey Milk Archives-Scott Smith Collection, LGBTQIA Center, San Francisco Public Library

In response to this harassment, gays and lesbians began to organize. At a 1971 community meeting to elect a new chair for the Eureka Valley Police-Community Relations Council, around fifteen long-time neighborhood residents were drastically outnumbered by the 300 gay men who showed up to the meeting. One of the anti-gay candidates for the position said he was, "fed up with all the hand-holding in the streets. My wife and child can't go outside without being scandalized." However, the gay constituency elected their own candidate, a restaurant owner who served a predominantly gay clientele. The next month, a front-page article declared, "San Francisco's populous homosexual community, historically nonpolitical and inward looking, is in the midst of assembling a potentially powerful political machine."

For the next three years, tensions were high in the neighborhood. Toad Hall and other gay bars were repeatedly damaged in suspicious fires. In July 1973, the home of the pioneering gay Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) burned to the ground. Police continued to arrest gay men for dancing in bars and clubs and cruising in parks. By 1974, the Gay Activist Alliance had recorded sixty beatings of gay people citywide in a three-month period, with the Castro having the worst record of all.

San Francisco Chronicle, 18 October 1971

Sign at San Francisco Pride Parade, 1977.

Credit: Shades of LGBTQIA, San Francisco Public Library

Relations between the gay community and the SFPD only deteriorated further after the assassination of Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone in 1978 by Dan White, a former police officer. When in May 1979 Dan White was convicted only of voluntary manslaughter — and not murder — initially peaceful demonstrations turned to riots. Several hours after the riots had been contained, police officers made a retaliatory raid on a bar in the Castro wearing riot gear, beating several patrons badly.

In the days that followed, the gay community’s leaders refused to apologize for the White Night Riots, and instead used their political power to help elect Diane Feinstein as mayor after she promised to appoint a pro-gay Chief of Police during her campaign. Feinstein followed through, and in the years that followed gay recruitment into the police force increased and tensions eased. But many other members of the queer community continue to have an uneasy relationship with law enforcement, particularly those who have experienced homophobic policing incidents in California.

Silhouettes of protestors outside City Hall during the White Night Riots, the evening of May 21, 1979, reacting to the voluntary manslaughter verdict for Dan White, that ensured White would serve only five years for the double murders of Harvey Milk and George Moscone. Credit: Danielle Nicoletta.

Want to Learn More?

Primary Source Set: Policing and Resistance, GLBT Historical Society

CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT FOR LGBTQ HISTORY IN SAN FRANCISCO, pp. 105 - 131

Season of the Witch, David Talbot