From Deportation to Repatriation

“We need their jobs for needy citizens”

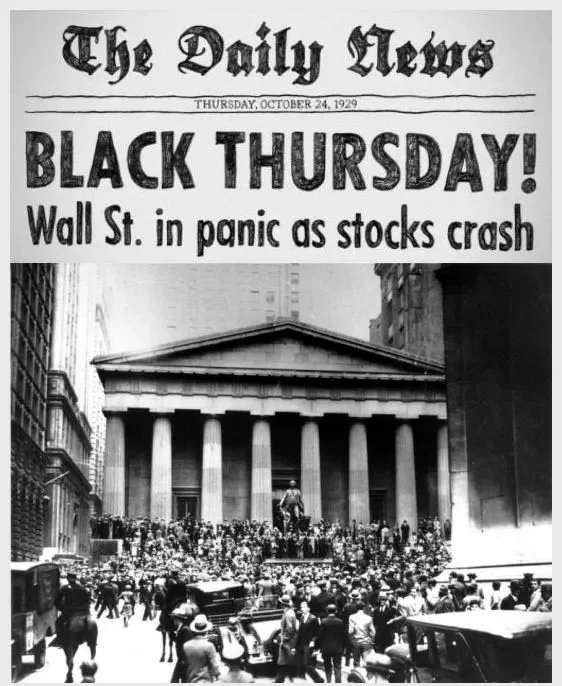

On October 24, 1929—just 6 months before Chrisine Sterling opened her Mexican marketplace—the U.S. crashed into the Great Depression. Unemployment skyrocketed across Los Angeles, and even those who kept their jobs suffered wage cuts and shortened hours. Every day welfare offices were flooded with more and more applications.

The Hoover Administration quickly became the lightning rod for public criticism and, pretty soon, the administration targeted immigrants as the scapegoats for a tanked economy. Hoover not only endorsed policies to restrict immigration, but also a concerted effort to expel “undesirable aliens” living in the US and allegedly holding down jobs that could belong to native-born Americans—an idea spearheaded by his new labor secretary, William Doak

After taking office in December 1930, Doak had announced that there were an estimated 400,000 of these “illegal aliens” in the United States, calculating that—under the provisions of the existing immigration laws—roughly 100,000 were eligible for deportation.

While the idea that the depression could be cured by expelling immigrants to return jobs to native-born Americans held little foundation in fact (not least because many of Doak’s targets in 1931 were themselves jobless and on relief), the concept gained quick traction.

Cover of The Daily News on 24th October 1929.

https://medium.com/@dhruv.shindhe/black-thursday-90-years-on-d054532a4c5e

Organizing in Los Angeles

With unemployment running high in Los Angeles, city and county officials, along with business leaders, concerned citizens, and the Chamber of Commerce created an ad-hoc relief committee in line with President Hoover's Emergency Committee for Employment (PECE). It was headed by Charles Visel.

Learning in early January 1931 of Doak’s proclamation against the 400,000 illegal aliens, Visel sent a telegram to the national coordinator of PECE, proposing a scheme to address the issue of “deportable aliens” living in Southern California. The telegram read:

“We note press notices this morning. Figure four hundred thousand deportable aliens United States. Estimate five per cent in this district. We can pick them all up through police and sheriff channels. Local United States Department of Emigration [sic] personnel not sufficient to handle. You advise please as to method of getting rid. We need their jobs for needy citizens.”

With the requested assistance from federal authorities, Visel devised a major publicity campaign around impending immigration raids. His plan was to raise alarm within immigrant communities, followed by some symbolic public arrests. In turn, “this apparent activity,” Visel’s telegram promised Doak, “will have tendency [sic] to scare many thousand alien deportables out of this district which is the result desired.”

A media frenzy around the threatened deportation raids transpired in the following weeks. “Aliens who are deportable will save themselves trouble and expense,” suggested the Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News on January 26th, 1931, “by arranging their departure at once.” On that same day, the Examiner announced that “Deportable aliens include Mexicans, Japanese, Chinese, and others.” La Opinión, the leading Spanish-language newspaper in Los Angeles, stressed that the deportation campaign was being disproportionately aimed at those of Mexican nationality.

The La Plaza Raid

Plans were drawn up for public immigration raids that – it was hoped – would scare immigrants out of LA for good. Thanks to the land border, fast train lines, and a friendly government, Mexicans were the easiest immigrants to remove.

On a sunny afternoon in late February 1931, La Placita Olvera was bustling with close to 400 people enjoying the fresh air. Suddenly, immigration agents—some in military uniforms, others in plain clothes—sealed off the exits. The agents demanded everyone in the park line up and show their papers. Families on the other side of the barricades ran to hide themselves in the basements.

The officers began questioning each person trapped behind the barricades, the majority of whom were Mexicans or Mexican Americans. According to La Opinión on 27 February, the dialogue went something like this:

Immigration officer: ¿Cuando entraste a los Estados Unidos? When did you enter the United States?

Mexican: Hace cinco años. Five years ago.

Officer: ¿Por cuál puerto? Which port?

Mexican: Por Nogales. Through Nogales

Officer: So, ¿Tienes papeles? So you’ve got papers then.

Mexican: No. Los perdí. I lost them.

Officer: ¿No tienes ni un papel que compruebe que me dices la verdad? So you don’t have a single paper to prove you’re telling the truth then…

Mexican: Todos los perdí. I lost them all.

This kind of story was common. The whole idea of an “illegal” Mexican was very new. Before 1917, there hadn’t been any kind of entry checks at all. Even afterwards, paperwork was perfunctory. Many Mexican residents didn’t have any papers to “prove” they were legal – because prior to recent changes to immigration law, those papers had never existed.

At the end of the questioning, immigration officers arrested about a dozen people, and deported a handful. But, the greatest impact of the 1931 La Placita Raid was psychological; it was the first large-scale, public immigration raid the city had seen. Its true purpose was to terrorize the community.

"“La Opinion” headline, February 27, 1931

Many Anglos believed that—although they wanted Mexicans to leave the city—the kind of public intimidation and arrest seen at La Placita was uncalled for. In October 1931, the government-appointed Wickersham Commission published a report highly critical of the Hoover administration’s deportation practices:

The apprehension and examination of supposed aliens are often characterized by methods that are unconstitutional tyrannic, and oppressive. There is strong reason to believe that in many cases persons are deported when further development of the facts would have shown their right to remain. Many persons are permanently separated from their American families with results that violate the plainest dictates of humanity.

In light of this kind of critique, Doak, Visel and other pro-deportation voices did change tactics, moving away from forceful deportation raids towards different, more insidious methods of expulsion. For the rest of the decade, increasing emphasis would be placed on coercing poor Mexicans to “voluntarily” return across the border.

Repatriation

Rather than supervise mass formal arrests and deportations, the Federal government’s plan shifted towards supporting city and state governments’ in coercing Mexican migrants to “voluntarily” return to Mexico. As the city with the largest population of Mexicans outside of Mexico, Los Angeles became the hotbed of the repatriation movement.

Similar to the media spectacle created by the anticipated raids, rumors and scare tactics were launched against Mexican places of business to drive people out of the country. Barrio grocery stores, for example, were targets of rumors that only US citizens would be allowed to cut or butcher meat. But, the efforts to remove Mexicans from the United States, particularly in Los Angeles, relied not only on scare tactics but on co-opting citizens into immigration policing and enforcement.

The LA County Welfare Office recruited a special group of employees—based on their Spanish language abilities and knowledge of labor and economic situations in California and Mexico—to encourage acceptance of repatriation. They knocked on door after door of Mexican families receiving aid, informing them that their access to public assistance would be cut off. Instead of welfare, they offered tickets back to Mexico.

Even Mexicans not on relief were pressured into accepting repatriation offers. Hospital orderlies, for instance, were asked to round up Mexican patients from local hospitals and bring them, via stretchers, to trucks that would transport them over the border. Mentally ill patients were no exception: Petra Sanchez Rocha was forced to accept repatriation after suffering a nervous breakdown. The staff at Los Angeles County Mental Health Center convinced her family that “her recovery could only be achieved in Mexico.” In some instances, coverage of burial costs were an incentive to return home, and there are accounts of gravely ill patients barely clinging to life before they reached their final destination in Mexico.

The first official repatriation train from Los Angeles, organized by the county Welfare Department, left on March 23rd, 1931. Local groups tried to make the departure as pleasant and festive as possible: church groups distributed toys to children; Occidental college students recited poems and performed dances; mariachis serenaded the repatriates. But, attempts to inject any sense of festivity into the situation was useless.

The overwhelming tone of the repatriados’ departure was somber, if not traumatic: men were quiet and pensive, while women and children cried; families said tearful goodbyes to loved ones; older children begged their parents to stay. In an oral history taken years later, Reverend Alan Hunter recalled:

“We had a feeling of it being totally unjust. We had a feeling – not of helplessness, exactly. All I remember is the vivid feeling of walking up one aisle of the train, seeing these people, and the feeling of hopelessness, but at least you were glad you were a human being, you could smile and let them know you cared. Maybe we cried. I know some people did. I’m a little ashamed I wasn’t more involved.”

Between 1929 and 1936, it is estimated that one-third of the Mexican population of Los Angeles – around 35,000 people – were “repatriated.” Nationally, the number of repatriates is estimated to be around one million. Mexican “Repatriation” in the 1930s violated a number of Constitutional provisions that apply equally to non-citizens, specifically 4th Amendment protections against unreasonable search and seizure and 14th Amendment guarantees of due process. More egregious still is the fact that an estimated 60% of those who were coerced into a “repatriation” to Mexico were American-born US citizens (a smaller number – around 2% – were naturalized Americans). These Americans were subsequently often denied reentry to the US unless they could present birth certificates or other documents proving citizenship.

Mexicans Migrants on the road with tire trouble (California, 1936). Photo by Dorothea Lange

Mexican and Mexican-American families wait to board Mexico-bound trains in Los Angeles on March 8, 1932. Los Angeles Public Library/Herald Examiner Collection

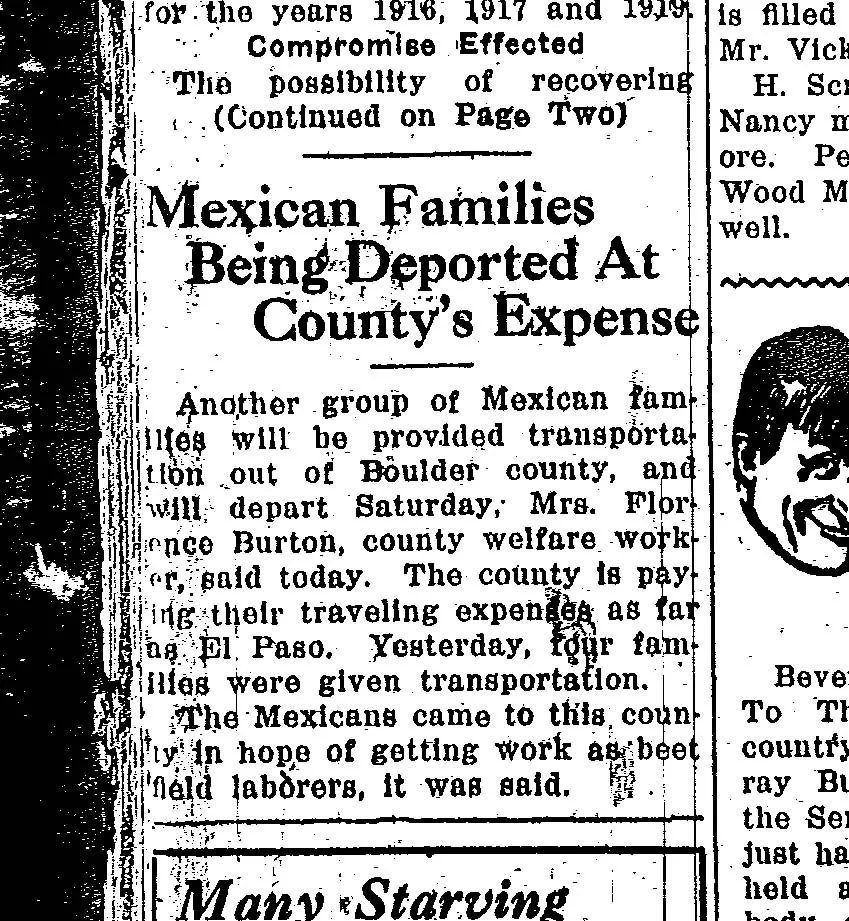

Newspaper report that another group of Boulder families will leave shortly, with their transportation costs covered, May 25, 1932. Courtesy of Carnegie Branch Library for Local History, Boulder

Generational Trauma

The experience of repatriation–whether through forcible deportation or soft coercion–was extremely traumatic for many of those removed from their homes. In particular, many of the hundreds of thousands of children who were returned to Mexico had been born in the United States, had never visited Mexico, and in some cases did not speak Spanish. Decade of Betrayal by Francisco Balderrama and a number of other studies, have documented the extent to which these removals and separations caused decades-long intergenerational trauma for the repatriados who struggled to find their place in either Mexico or America, or who suffered abrupt family separation.

Emilia Castañeda who was just a small child when her father decided his only option was to take her and her siblings back to Mexico, recalled the sense of “ni de aqui, ni de allá” that the experience of repatriation caused:

“They used to say that I was atiriciada. I guess it’s something like depressed. Maybe I was homesick. A lot of people did discriminate against us because we were Americans. We didn’t belong there. Isn’t it strange? Here, the Anglos discriminate against us because we’re Mexicans. So, really, where do we belong?”

Emilia Castañeda, c. 1945

Want to Learn More?

Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s, by Francisco E. Balderrama and Raymond Rodriguez

Unwanted Mexican Americans in the Great Depression: Repatriation Pressures, 1929–1939 by Abraham Hoffman