The Rise of The Castro

“Gayborhood”

Eureka Valley, intersection of Castro and Market, 1944.

Credit: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

As we hear in At Home in the Castro?, until the 1960s, Eureka Valley was home to a sleepy but tight-knit Irish Catholic community. It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when and why a transformation began to happen. Some say there was a general exodus of the old residents already underfoot by this time: the rise of cars allowed white middle class families to move out to the suburbs and still commute to the city for work. Others say the conservative Eureka Valley residents feared the hippies in the Haight were coming over the hill. San Francisco also built up its financial sector in the 1960s, thinning ethnic neighborhoods and drawing mobile, college-educated young people to fill white-collar jobs that replaced the city’s former manufacturing industry. In any case, by the late 1960s, inexpensive Victorians were available to let or to buy. Eureka Valley was also a neighborhood where dozens of business premises still held liquor licenses even though the pubs themselves were shutting down (San Francisco was notoriously slow to approve new liquor licenses). All this created prime conditions for many of San Francisco’s queer community to move south to the Castro. Many members of the queer community that had centered on Polk Street and the Tenderloin were looking to escape a neighborhood struggling with crime and deprivation, where street life had been disrupted by downtown construction work.

Balloons being released from rooftops on Castro Street, Castro Street Fair 1976.

Credit: Shades of LGBTQIA, San Francisco Public Library

As young gay people made their way from all over the country, the little village on the slopes of Twin Peaks began to transform into something the world had never seen: a gay hometown. One by one, Eureka Valley businesses gave way to new owners, with a new clientele. The maternity shop became a trendy men’s clothing store, “All American Boy.” The Castro Theater began showing classics and art films. When the Most Holy Redeemer Church didn’t exactly welcome their new neighbors, they formed the Metropolitan Community Church. Two lesbians bought the Twin Peaks Bar in the early 70s, installing plate-glass windows: the first gay bar in the nation where the patrons were on full view for the world to see.

Events in the Castro – street fairs, pride parades, Halloween parties – became nationally advertised gay holidays. Tourists came in floods to witness this new “gay Mecca,” often choosing to stay. By 1977, as many as 20,000 gay people had moved into the neighborhood to join what was now a full-fledged movement for gay liberation, hatching a brand new culture along the way.

“I had read in an old issue of Life Magazine, in 1971, that gay people were moving to San Francisco and I’d heard vague references of homosexuals in San Francisco. So it seemed to me that this was a place of refuge...

...Oh, this was a different planet. Everything about San Francisco was different, from the glitter in the sidewalks to the way the fog rolled in, to the fact that you could see other people on the street that you knew were gay.”

The New In-Group

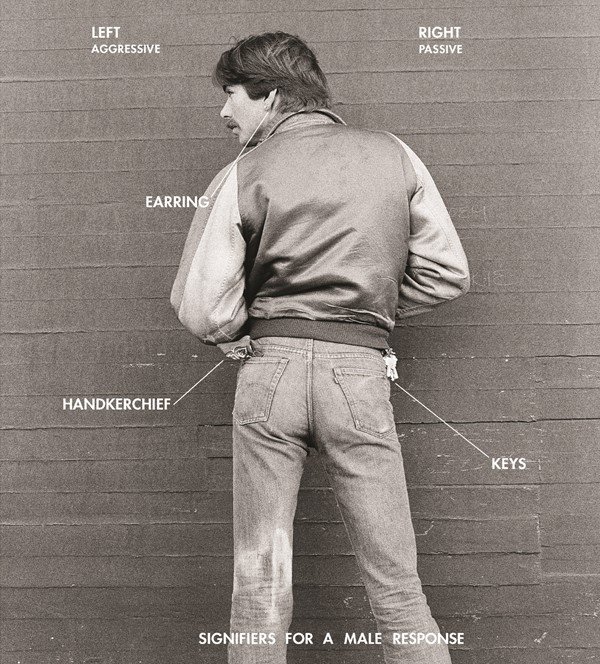

Hal Fischer, Signifiers for a Male Response, 1977

By the summer of 1978 – what some recall as the high point in the Castro’s development – a new society had taken shape. The new immigrants came from mainstream, mainly white America, and they brought their institutions with them: there were gay softball leagues, a gay chorus, and three gay and lesbian newspapers. They also developed a new style of dress and behavior, what came to be known as the “Castro Clone” look. Men sported short hair and mustaches. They wore white T-shirts, Levi’s jeans, and hiking boots. Bodybuilding became the trend. A new in-group identity was established in the neighborhood, which came with a whole new set of exclusions.

The Castro’s new residents were predominantly white and overwhelmingly male. Within the new culture, people of color staked out their own small havens, like the Pendulum bar, but they were few and far between. Similarly, most lesbians did not feel welcomed. Effeminate men, trans men and women, or people dressed up in drag routinely faced discrimination in bars and on the streets.

The new culture also redefined mainstream America’s taboos around sex. In the Gayborhood, sex was a positive thing, rather than a source of shame and secrecy: and sex was everywhere in the Castro. The ubiquity of gay bars, bathhouses, and sex clubs provided abundant opportunities to meet up for frequent, anonymous sex. The Castro clone look itself was an invitation for sex, and different accessories—a red or blue handkerchief, keys worn on the right or left side, stud earrings–were all codes for sexual preference.

“…I wanted to move away because... we came to get out of the closet and... it was the most narrow-minded group of people in the world, I thought. You had to dress for them, you had to look like them, you had to — everybody had attitude. Nobody related to people in those days. It was like sex and that’s it.”

1980s: A Strange Cancer

In the early 80s, a series of pictures hung in the window of Star Pharmacy–now the Walgreens on 17th and Castro–depicted a young man with strange skin lesions. The photographs warned the neighborhood of a new “gay cancer” which was cropping up first in dozens, and then hundreds of gay men in San Francisco. The lesions turned out to be Kaposi’s sarcoma, a rare skin cancer characteristic of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

The Castro was ground zero for HIV/AIDS in San Francisco, which spread through the exchange of blood and other body fluids. But little was known about the epidemic at the time, and the national response was slow. Right wing congresspeople, the Moral Majority, and Fundamentalists went as far as declaring the disease a divine punishment from god.

With little support from the U.S. healthcare system, the concerted response to AIDS largely came from within San Francisco’s LGBT community. Lesbians organized drives to donate blood to the gay men affected by AIDS. Neighborhood volunteers stepped in for the caregiving tasks typically assigned to family members, visiting the houses of the sick, bringing food, cleaning, and delivering medication.

AIDS devastated the Castro; a decade after Star Pharmacy posted the cautionary photographs, nearly half of San Francisco’s gay community had been lost to the illness. Nationally, the death toll climbed above 100,000. While the extent of tragedy caused by HIV/AIDS is difficult to quantify, the decade following 1980 can also be seen as a final stage in the Castro’s development as a neighborhood: in a community shunned the healthcare system, governmental support, and even their own families, queer people created their own structures of belonging and support.

Men in the Castro gathered around public fliers raising awareness about AIDS. Credit: Rink Foto

Gentrification and Rainbow Capitalism

The rise of the Castro also changed the economic landscape of the neighborhood: beginning in 1973, the price of residential property climbed sharply. By 1976, the old houses were fetching five times their value. In 1977, the rent on Milk’s camera store had tripled, ironically forcing him to move his store to Market Street. While once a haven for bohemians and social activists, the businesses on Castro street came to include an expensive shop for home decor, a wine-and-quiche café, and trendy clothing boutiques. Today, the median house price in the Castro stands at over 1.5 million dollars.

As the neighborhood gentrified, all kinds of families were drawn to the Castro, making the demographic now older and quite wealthy. And while rampant commercialism advertises the Castro strip–with its rainbow flags and raunchy business names–as a “gay mecca,” the neighborhood has been described as a mirage: it's no longer a gay neighborhood, but a gay theme park geared towards tourists and their pocketbooks. Moreover, as more corporate sponsorships leak into pride festivities, some fear that symbols of gay culture have become part of a global “brand” from which corporations have benefited.

Google employees carry rainbow flags as they march in the San Francisco Gay Pride parade in 2013. Credit: Eric Wagner

Want to Learn More?

A Walk on San Francisco’s Gay Side, New York Times

The Castro, New Yorker, Frances Fitzgerald

San Francisco Aids Foundation History in Pictures

Don't Let That Rainbow Logo Fool You: These 9 Corporations Donated Millions To Anti-Gay Politicians, Forbes, Dawn Ennis